Notable Heydeckers

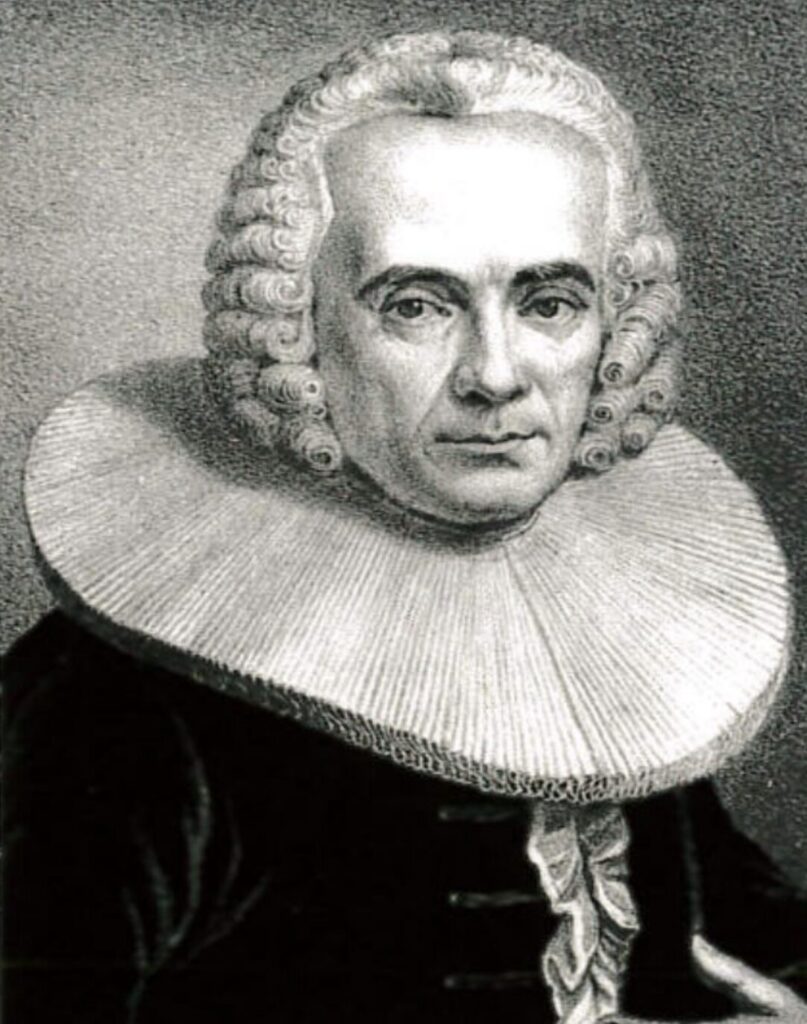

Hans Konrad Heidegger

Now, let us turn our attention to Hans Konrad Heidegger (1710 – 1778), who is esteemed as one of the most distinguished members of our lineage. In the year 1768, he attained the zenith of honor within the Republic of Zurich, assuming the esteemed office of Mayor. A true embodiment of enlightened authority, he executed his duties with rigor, a standard he likewise expected of others. During his time in office, he orchestrated the reorganization of Zurich’s entire system of schooling, as well as the somewhat precarious mortgage industry. Indeed, Bank Leu & Co. AG, a venerable institution still thriving in Zurich today, traces its origins back to this very endeavor.

He played an active role in the establishment of the Usury Natural Research Society, from which he earnestly hoped to foster scientific advancements for the betterment of agriculture. In truth, he maintained close ties with the peasantry, assisting them in adopting new methods and tools to enhance their yields. The Mayor also held the esteemed position of President of the library convention, and the library was considered his most cherished pursuit.

Heidegger’s son, also bearing the name Hans Konrad (1748 – 1808), was a significant collector of art. He held several important high state offices within Zurich, before settling in Munich after the year 1795. It is said that in 1803, King Maximillian Joseph bestowed upon him both title and property within that city.

(As translated by the Right Honourable Lady Jeanne-Elise M. Heydecker from the original German of “Heydecker Genealogisches Arbeitsbuch” penned by Joseph Julius Heydecker and curated by Sebastian Heydecker, a document currently held within the European Union.)

Louis Pfyffer von Heidegg

Now we turn our attention to Louis Pfyffer von Heidegg, a scion of an ancient patrician family of Lucerne, who first saw the light of day in Naples in the year 1838. There, he joined the Swiss regiment, serving until a chronic ailment of the foot compelled him to resign his commission as lieutenant at the tender age of twenty-one. Upon his return to Lucerne, he took up a position as an official with the central railway. Following his marriage to Caroline Slidell, his attentions soon turned to the administration, enlargement, and embellishment of his ancestral castle estate.

His wife, Caroline Slidell, was born in New Orleans, in the American lands of Louisiana, in the year 1850. Her father, John Slidell, originally from New York, was a man of law, a senator, and a landowner. Her mother’s forebears, the Mathilde Deslondes, hailed from the ancient lands of Normandy. This noble couple and their four daughters were to be the last family to both privately own and reside within the venerable Schloss Heidegg.

Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) was a German philosopher whose work profoundly shaped 20th-century thought, especially in phenomenology, existentialism, and hermeneutics. His seminal text, Being and Time (1927), introduced the concept of Dasein, a unique mode of human existence. Born in Meßkirch, Baden, Heidegger was raised Catholic and began theological studies before shifting to philosophy at the University of Freiburg. He completed his doctorate in 1914 and qualified to teach with a thesis on Duns Scotus in 1916.

After brief military service during WWI, he was appointed professor at the University of Marburg in 1923, where he influenced many future thinkers, including Hans-Georg Gadamer, Hannah Arendt, and Leo Strauss.

Heidegger’s personal life was complex. He married Elfride Petri in 1917, though maintained extramarital relationships, most notably with Hannah Arendt and Elisabeth Blochmann. His political affiliations remain controversial: he joined the Nazi Party in 1933 and served briefly as rector of Freiburg University. Though he resigned a year later, he remained a party member until 1945. His writings and speeches during this period expressed support for the regime, and later revelations from his Black Notebooks (published posthumously in 2014) exposed anti-Semitic elements in his philosophy.

Following WWII, Heidegger was banned from teaching until 1951, after which he returned to Freiburg, eventually becoming professor emeritus. Known for his love of the outdoors, he often taught while hiking or skiing. He died in 1976 in his hometown of Meßkirch.

Joseph Julius Heydecker

Joseph Julius Heydecker (1916–1997) was a German writer, photographer, journalist, and publisher whose life and work were deeply shaped by the rise and fall of the Nazi regime. Born in Nuremberg, he came of age during the rise of Adolf Hitler and was conscripted into the German military during World War II. While serving in Warsaw, Heydecker secretly photographed life inside the Warsaw Ghetto, risking his life to document the suffering and dehumanization imposed on the Jewish population. These haunting images, taken with a concealed camera, would later become some of the most important photographic evidence of life under Nazi occupation.

After the war, Heydecker became a journalist and played a significant role in covering the Nuremberg Trials, where he reported on the prosecution of major Nazi war criminals. He collaborated with fellow journalist Johannes Leeb on The Nuremberg Trial: A History of Nazi Germany as Revealed Through the Testimony at Nuremberg (1958), which provided readers with a comprehensive account of the trials, blending historical context with verbatim testimony. He was one of the earliest postwar German voices to confront the horrors of the Holocaust and the Nazi regime, and his writing contributed to the broader process of Vergangenheitsbewältigung—Germany’s reckoning with its past.

Heydecker later settled in Vienna, where he continued to write and reflect on his wartime experiences. His books, including The Warsaw Ghetto: A Photographic Record and Moja Wojna, offer a rare perspective from a German soldier who became a witness rather than a participant in atrocity. His life and work serve as a poignant reminder of the power of individual conscience, even in the darkest of times.